Long before the giant tunneling machines nicknamed “Big Bertha” in Seattle and “Lady Bird” in Washington, D.C. and “Miss Colleen” in Maryland, there was the very simply named “Beach tunneling machine.” Designed in the late 1860s by a skinny, mustachioed, opera-loving inventor in New York City named Alfred Ely Beach, it was, as far as we know, the first tunnel-boring machine used in the United States.

Long before the giant tunneling machines nicknamed “Big Bertha” in Seattle and “Lady Bird” in Washington, D.C. and “Miss Colleen” in Maryland, there was the very simply named “Beach tunneling machine.” Designed in the late 1860s by a skinny, mustachioed, opera-loving inventor in New York City named Alfred Ely Beach, it was, as far as we know, the first tunnel-boring machine used in the United States.

Alfred Beach wanted to build a subway tunnel for New Yorkers, and the only obstacle standing in his way was a powerful one in the form of a 300-pound corrupt state senator known as Boss Tweed. So Beach did what he had to do in order to defy Tweed. He built a tunnel in total secrecy, right under Boss Tweed’s nose, with an army of workers digging in the middle of the night in the basement of Devlin’s Department Store. It was the ultimate David vs. Goliath tale.

The folks in Seattle who are steamed about how much money is being wasted because Bertha sits idle and stalled underground and no one has a clue how to fix it or move it should take heart. Maybe the story of Alfred Beach will give them hope. His story of perseverance and ingenuity is amazing. It’s the first chapter in my book, “The Race Underground,” and personally it’s my favorite.

Here is a quick excerpt:

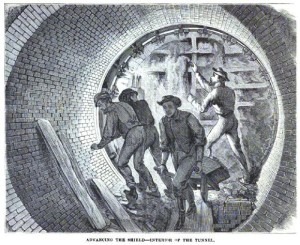

The device he came up with was ingenious. It resembled a hollowed-out barrel, used a water pump to exert pressure and a sharp digging mechanism that could loosen 16 inches of soil with each push forward. He also designed a metal hood over the edge of the shield that would protect his workers from falling debris, or in the catastrophic event of a collapse.

In late December of 1869, Beach, his son, Frederick, whom he tapped to be the foreman of the project, and a small group of men started arriving at Devlin’s after the store had closed for the night. They brought down picks, shovels, covered wagons, bricks, lanterns and other tools. Following Beach’s instructions to tunnel south directly under Broadway from Warren Street and then curve slightly to just below Murray Street, the laborers worked quietly to avoid rousing suspicion on the streets above. Night after night, six men would stand inside the shield, while another half dozen would perform the more tedious tasks to polish the tunnel. Some carried out the dirt in the covered wagons, others laid the bricks to line the tunnel, and still others laid the tracks to carry a single car. The walls were painted white, iron rods were installed through the tunnel’s roof up to the pavement, and gaslights and oxygen lamps were hung. It was an efficient operation. But it was also scary work, too claustrophobic for some workers who simply walked off the job. The rumbling from a street railway’s wheels overhead created a terrifying roar that made the late-night work nerve-wracking. Still, thanks to surprisingly soft soil and the efficient tunneling shield, the digging went quickly. On a good night, one crew would dig forward eight feet.

Just like in Seattle everything was going smoothly. Until one night, Beach’s shield buckled and the ground shook. The soft dirt ended and the workers stared at a mysterious stone wall in front of them.

It was an old Dutch fort from before the Revolutionary War. Beach faced a dilemma. Either the wall had to come down or the project was over. And nobody knew if removing the wall would cause Broadway to buckle or collapse from above.

What did Beach do? Like I said, it’s my favorite chapter. There is a very detailed description of Beach’s shield here, and more details in my book, as well.

It took centuries for mankind to embrace tunneling, to believe that it was safe to go underground and travel through dark tunnels. But it’s safe to say those fears are long gone. Today tunneling is more popular than ever. Washington, D.C. is digging away to create a huge sewage system. A highway tunnel in Seattle is underway. The Second Avenue Subway in New York is a few years from completion. In Canada, workers dug under Niagara Falls to expand a hydroelectric-generation complex. In Russia, there’s a new wastewater tunnel under a St. Petersburg river.

All of these projects became possible because of what are now commonly known as TBMs, or tunnel boring machines. Each one has to be designed and built specifically for its project, because of the ground they must bore through, the size and shape of the tunnel needed, and other factors, making them enormously expensive. And when they get stuck, like Bertha, those costs become astronomical. Persistence and patience, two qualities that Beach exhibited in 1869 and 1870 in the pursuit of his secret subway, are two qualities that would serve Seattle residents well in these trying times.