New Book Project! World War II Liberty Ships

Journalist, author, editor, storyteller

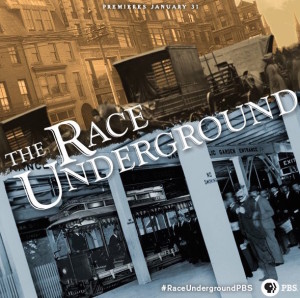

In advance of the American Experience premiere airing of “The Race Underground”, Michael Rossi’s hour-long documentary on the birth of Amreon Tuesday evening, January 31 (based on my book by the same name), PBS released a short trailer today! Enjoy.

OK, set your DVR if you’d like. Tuesday evening, January 31, at 9 p.m., WGBH TV will air the documentary “The Race Underground” based off of my book of the same title. Yes, I’m excited. It’s hard to believe, but this project I undertook is now stretching into its 7th year! Geez.

OK, set your DVR if you’d like. Tuesday evening, January 31, at 9 p.m., WGBH TV will air the documentary “The Race Underground” based off of my book of the same title. Yes, I’m excited. It’s hard to believe, but this project I undertook is now stretching into its 7th year! Geez.

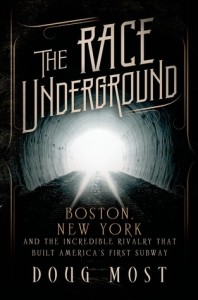

It started with an idea for a book. Then a year writing a book proposal and selling it to St. Martin’s Press. Then two years writing the book, which came out in February 2014 to positive reviews. Then the paperback came out in 2015. And now the documentary. The Matt Damon movie, well, still waiting on that one!

I’ve seen the film, which is almost an hour long, and it’s remarkable (if they finish a trailer for it, I’ll be sure and post that, as well). It was produced by Michael Rossi, a North Shore filmmaker as I’ve written here before, and he pulled together half a dozen great interviews, myself included, as well some incredible new research and graphics, to weave a great story. It doesn’t tell the story of the whole book about the rush to build America’s first subway between Boston and New York, but rather he zooms in on one of my favorite characters, the unsung hero Frank Sprague.

So the first showing will air January 31, but if you miss it, or forget to record it, don’t worry, there are plenty more times. Here is the entire PBS schedule of airings.

| Wed. Feb 1 at 5:00 AM | WGBH 2 | |

| Sun. Feb 5 at 12:30 AM | WGBH 2 | |

| Sun. Feb 5 at 3:00 PM | WGBH 2 | |

| Wed. Feb 1 at 2:00 AM | WGBX 44 | |

| Wed. Feb 1 at 1:00 PM | WGBX 44 | |

| Thu. Feb 2 at 4:00 AM | WGBX 44 | |

| Fri. Feb 3 at 3:00 AM | WGBX 44 | |

| Sat. Feb 4 at 2:00 PM | WGBX 44 | |

| Sat. Feb 4 at 9:00 PM | WGBX 44 | |

| Fri. Feb 3 at 8:00 PM | WGBH WORLD | |

| Sat. Feb 4 at 1:00 AM | WGBH WORLD | |

| Sat. Feb 4 at 9:00 AM | WGBH WORLD | |

| Sat. Feb 4 at 3:00 PM | WGBH WORLD

|

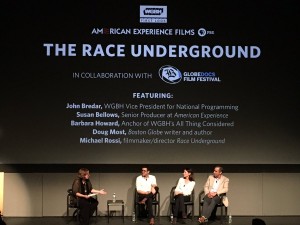

The film aired in early November during HubWeek at the Globe Docs Film Festival, and we had a fun evening with a panel talking about the film and the broader story (here is a photo from that night).

And finally, here is the summary of the documentary from “American Experience.”:

In the late 1800s, Boston reigned as America’s most crowded city, with nearly 400,000 people packed into a downtown of less than one square mile. With more than 8,000 horses pulling the trolleys, the city was filthy and noisy, reeking of manure and packed with humanity.

But a young American inventor named Frank Sprague had a revolutionary idea. Inspired by his visits to the London Underground, Sprague envisioned a subway system that would trade London’s soot-spewing coal-powered steam engine with a motor run on the latest technology — electricity. After an early job with his idol Thomas Edison, Sprague launched his own venture, the Sprague Electric Railway & Motor Company. Seeking investors, he first struck out with financier Jay Gould after almost setting the mogul on fire during a demonstration. He soon found backing with the wealthy capitalist Henry Whitney, who owned a fortune in suburban Boston real estate and quickly saw the financial upside of connecting his desirable residential neighborhoods with the city’s economic center. Whitney also proposed the consolidation of Boston’s seven existing streetcar companies — all under his control. When the Massachusetts General Court granted Whitney the monopoly, he announced an unprecedented plan – to build the nation’s first subway. Powered by Sprague’s technology and enthusiastically supported by Boston Mayor Nathan Matthews, the project threw the city into a voluble debate.

”The Boston subway was not a foregone conclusion, not by a long shot. There was a petition at one point where 12,000 businessmen opposed the subway,” says historian Stephen Puleo. ”There were going to be streets torn up, sewer systems affected, water lines affected, electrical lines affected. Secondly, folks felt like traveling underground was very close to the netherworld, that you were getting closer to the devil, that you were taking this great risk in God’s eyes by traveling on a subway.”

The debate raged on, but the Mayor finally convinced the city that the new subway would provide much-needed jobs and not infringe on the city’s beloved Boston Common. After two years of construction, Boston’s new subway made its first trip on September 1, 1897. Despite lingering fears, more than 250,000 Bostonians rode the underground rails on its first day. In its first year of operation, 50 million passengers would ride the Boston system, and within ten years, New York and Philadelphia opened subways, with more American cities to follow.

”Frank Sprague lived in the shadow of Edison but played as important a role in the development and growth of cities as any person in our history,” said author Doug Most. ”His motor is one of the most important contributions, right there alongside Henry Ford’s vehicle and the Wright Brothers’ plane, as one of the most important engineering achievements of our time.”

I haven’t had too much to update on Michael Rossi‘s documentary “The Race Underground,” coming from PBS and American Experience, but now I do. The first screening of the documentary is happening Saturday evening, October 1, at 7 p.m., as part of the GlobeDocs Documentary Film Festival.

I haven’t had too much to update on Michael Rossi‘s documentary “The Race Underground,” coming from PBS and American Experience, but now I do. The first screening of the documentary is happening Saturday evening, October 1, at 7 p.m., as part of the GlobeDocs Documentary Film Festival.

I’ve seen a rough cut of the film, but not the final version yet. What I saw, I loved, and Michael did an incredible research job on top of my own for the book. The movie focuses on the Boston subway, and is less about New York’s, which makes for a tighter, more focused storytelling experience.

GlobeDocs is an incredible collection of documentaries from around the country, so it’s an honor to have “The Race Underground” included. The event is free, but you still need to reserve tickets, which you can do by clicking here. It’s being shown at the beautiful WGBH Yawkey Studio (photo above), directions here. As with everything I’ve posted about “The Race Underground,” thanks for sharing the news, and thanks so much for all your support.

So this is sorta cool. The West End Museum, which describes itself as “a neighborhood museum dedicated to the collection, preservation and interpretation of the history and culture of the West End of Boston,” is doing an event with me in September (Sept. 14 at 6:30 to be precise). It makes perfect sense because the first subway in America, Boston’s, was the result of a company created by Henry Whitney called the West End Street Railway Company. And Whitney is a key figure, of course in my book, “The Race Underground.”

So this is sorta cool. The West End Museum, which describes itself as “a neighborhood museum dedicated to the collection, preservation and interpretation of the history and culture of the West End of Boston,” is doing an event with me in September (Sept. 14 at 6:30 to be precise). It makes perfect sense because the first subway in America, Boston’s, was the result of a company created by Henry Whitney called the West End Street Railway Company. And Whitney is a key figure, of course in my book, “The Race Underground.”

In advance of this event, we’ve put together a fun trivia contest. The link is here, go play!

And all the details on the event can be found by clicking here.

By the way, if you know Back Bay, Beacon Hill, the South End, the North End, but you have no idea where the West End is or what the West End is, you should know! It’s a huge part of Boston’s history. Here is a description, from the museum:

The history of the West End is one of a largely immigrant neighborhood displaced or destroyed by ‘Urban Renewal‘ in a campaign that saw a third of Boston’s downtown demolished between 1958 and 1960, but it’s also the history of a diverse community that produced several influential people, boasted a unique culture and included many places of historical significance.

Among the few famous Bostonians to come out of the West End include Leonard Nimoy (Spock), Sumner Redstone, and Charles Bulfinch.

This map outlines the West End’s boundaries.

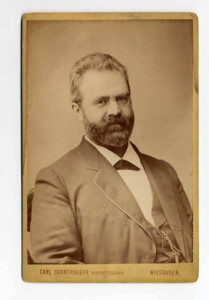

When you think of the biggest names who influenced life in New York City, names like LaGuardia, Rockefeller, Parsons, Belmont, Moses are usually among the first mentioned. Squire Vickers (an old shoot of him at right) is not on that list. But as a great story in the New York Daily News shows, he should be.

When you think of the biggest names who influenced life in New York City, names like LaGuardia, Rockefeller, Parsons, Belmont, Moses are usually among the first mentioned. Squire Vickers (an old shoot of him at right) is not on that list. But as a great story in the New York Daily News shows, he should be.

Here is how staff writer Keri Blakinger explains it nicely:

You’ve probably never heard of him, but an eccentric man from Rockland County is one of the people most responsible for the look and feel of the New York City subway system.

Squire Vickers, the system’s chief architect for more than three decades, oversaw the design of more stations than any other individual — and he left his stamp on the system, with signature tile station plaques and a distinct Arts and Crafts design that permeates the system to this day.

Essentially he oversaw the design of hundreds of the stations that were part of the system designed by another famous New Yorker, William Barclay Parsons, whose name is now familiar through the engineering firm he founded, Parsons Brinckerhoff, which designed, among many projects, the Cape Cod Canal and the Panama Canal. Parsons deserves the credit for designing the subway system, and even details like where to put the doors on the subway cars, but the little-known Vickers played a huge role in the layout and design of the stations passengers walk through. And those iconic plaques that instantly identify New York’s subway as unique.

This is pretty cool. New York Magazine’s Vulture website has compiled 20 great moments from the movies that take place on New York’s subways. Here is the link. I will save this list for when my book comes out as a PBS “American Experience” documentary, which is getting closer and more exciting.

Quick thoughts on Vulture’s list: Glad to see Pelham 123 high on the list, great movie, great subway scenes, a natural for a list like this. But since Vulture focuses only on New York subway scenes, I immediately thought of non-New York subway scenes. Here are a few classics.

The Fugitive fight scene with Harrison Ford.

I can’t find a clip from this, but the scene in Good Will Hunting when Matt Damon rides the Red Line over the Longfellow Bridge. This scene is famous because it’s been cited as a gaffe, because the camera angles are not possible from the direction of the train. But still a memorable scene for Bostonians.

Another great movie scene in a subway that became famous for not being accurate is No Way Out, starring Kevin Costner as a double agent in Washington, D.C. The scene essentially made up subway stations in the Georgetown neighborhood, which anybody who lives in DC knows do not exist.

Back to New York, however, and one of the scenes Vulture lists definitely goes down as one of the spookier ones I remember watching. It’s from Ghost. Remember this?

It would be called the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, or BQX. And in his State of the City address, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his support for this 16-mile, $2.5-billion streetcar line that would run along the East River and connect Astoria, Queens, with Sunset Park in Brooklyn. (This story on the wonderful Awl website has the details.)

It would be called the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, or BQX. And in his State of the City address, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his support for this 16-mile, $2.5-billion streetcar line that would run along the East River and connect Astoria, Queens, with Sunset Park in Brooklyn. (This story on the wonderful Awl website has the details.)

It immediately stirred up debate about whether that transit project, of all transit projects being discussed in New York City, is really the one that makes the most sense and would serve the most people.

I won’t get into that debate. But what’s undeniable is that a trolley to Queens would be a quaint reminder of where New York’s subway, which opened in 1897, has some of its roots laid. And those roots are in Queens. It’s one of my favorite stories in The Race Underground involving one of my favorite characters.

His birth name was Wilhelm Steinweg (that’s him above). He was born on March 5, 1835, the fourth of six children in a tiny German village called Seesen. The father of those children, Heinrich Steinweg, made pianos for a living and one day he dreamed of bringing all of his children into the family business. But when his third son, Charles, was at risk of going to war as Europe was awash in revolutions, Charles fled for New York, joined the piano-making industry there, and wrote home to his family that they should come, too, because the piano factories in the city were thriving.

And so they did. In the summer of 1850, the Steinweg family sailed into New York’s harbor, and not long after that the family name was anglicized into Steinway and a piano manufacturing behemoth was born. One of Charles’ brothers, William Steinway, helped the family grow its business with a manufacturing plant in Queens. It was William’s ability to juggle so many tasks, to disarm anyone he came in conflict with, and to convince politicians to give him what he wanted, that caught the attention of New York politicians in the late 1800s, as efforts ramped up to get a subway approved and built. William Steinway was named to head New York’s Rapid Transit Commission of 1891 and the next decade, his relationship with the brilliant engineer, William Barclay Parsons, and their efforts to bring New York a subway, became an enormous part of Steinway’s legacy.

And it all started in Queens. This is from the great Henry Z. Steinway Diary Project at the Smithsonian: A desire to remove employees from Manhattan’s teeming humanity, particularly organized labor and “the machinations of the anarchists and socialists,” inspired William to purchase 400 acres across the East River in a bucolic, sparsely-populated area of Astoria, New York. With space for much-needed expansion, William set about creating the company town of Steinway where the firm could cast its own piano frames and saw its own lumber. Steinway & Sons pianos are still manufactured at this location. William approached the development of Steinway with characteristic thoroughness, wading through rainy salt meadows in “great India rubber boots” inspecting property, overseeing street surveys, and assessing employee housing construction later advertised as “country homes with city comforts.” Diary entries reflect William’s pride in creating a company town where workers could own brick homes, drink fresh water, and stroll under shade trees on Steinway Avenue—still the main thoroughfare in this part of Queens. He donated land and built a public school, fire house, post office and churches to further his vision. A network of horse-car railroads, streetcars, trolleys, and ferries provided access to the settlement and brought in additional income. What would become North Beach Amusement Park offered “respectable people” an alternative to Coney Island and the chance to experience evening festivities illuminated by the novelty of electric lighting.

And finally, here is the Steinway family at their beautiful stone mansion in Astoria, Queens.

So whether or not the BQX is the best move for New York may be debatable. But what’s undeniable is that a street trolley in Queens would have a certain karma for Gothamites, who owe a great deal of transit debt to a businessman who started in Queens.

It’s happened to all of us. You’re sitting on the subway, it’s the end of a long day, the vibrations of the tracks are surprisingly soothing, your eyes start to dim and finally, zzzzzzzzzzzzz. You’re out.

Is sleeping on the subway really so bad?

Apparently in New York City it is. Police Commissioner Bill Bratton has vowed no more subway snoozing! Half the crimes on the subway, he reports, are committed on people sleeping. “Subways are not for sleeping,” Bratton said at a recent news conference. “I know people have gotten out of work and are tired but we are going to start waking people up.”

That might mean waking up a lot of people.

Check this out from the New Yorker piece titled: “Let us Sleep on the Subways!” Where once there were lonely cars at lonely times, now the subways seem as packed at four in the morning as at five in the afternoon. Saturdays and Sundays, where once one could always find a space on the sideways banquette of the E train, one finds it now as mobbed as at any weekday rush hour. This is no illusion or impression, either. The numbers are daunting. In 2014, around 1.75 billion—that’s right, billion—riders used the trains, the largest number since 1948. Much of the growth from the previous year was concentrated, unsurprisingly, in the rapidly growing neighborhoods of Brooklyn—or, to put it in plain English, in the unending tsunami of hipsters travelling to and from what were once quaintly called the outer boroughs. A generation has mastered the trains. Where it used to be impressive if a non-native New Yorker could work a transfer hookup involving much more than the Times Square shuttle, now newcomers talk easily of changing for the Q and hopping on the M and even of cruising out on the Z. A new world.

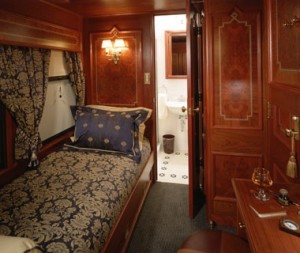

For those who demand to be left alone to their sweet subway dreams, there is clearly only one solution left: Demand your subway install one of these on every subway train! Sleeper cars for everyone!

On September 1, 1897, America’s first subway opened in Boston, when a trolley disappeared underground at the corner of Arlington and Boylston streets and stopped at a station at the corner of Boylston and Tremont. (At left is a picture of a trial run the day before.)

On September 1, 1897, America’s first subway opened in Boston, when a trolley disappeared underground at the corner of Arlington and Boylston streets and stopped at a station at the corner of Boylston and Tremont. (At left is a picture of a trial run the day before.)

On January 14, 2016, the Boston subway system recorded a very different milestone: The National Transit Database released data that showed the MBTA had 219 “major mechanical failures” in the year 2014. That’s the worst rate of breakdowns among all transit systems nationwide, and it’s four times the national average. Yikes.

The Red Sox went worst to first to worst in three seasons. What are the odds the MBTA climbs to first next year?

As reported in The Boston Globe: MBTA spokesman Joe Pesaturo questioned the national figures, saying that “there is no uniform practice for reporting mechanical failures” to the National Transit Database. “What one rail service provider considers a failure, another one may not,” he said. He also said the agency would continue efforts to keep old trains and equipment from failing by either repairing or replacing them.

Also from the Globe:

The T’s light rail lines — the Green Line and Mattapan-Ashmont trolley — ranked third worst in terms of major mechanical system failures per train mile traveled among 23 light rail systems nationally, according to the 2014 National Transit Database, which is maintained by the Federal Transit Administration. The T’s heavy rail lines — the Red, Orange, and Blue — ranked as the sixth worst among 15 heavy rail systems nationally, the figures show. The commuter rail system ranked fifth worst among 24 commuter rail systems nationally in 2014, the latest year for which data was available.