It would be called the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, or BQX. And in his State of the City address, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his support for this 16-mile, $2.5-billion streetcar line that would run along the East River and connect Astoria, Queens, with Sunset Park in Brooklyn. (This story on the wonderful Awl website has the details.)

It would be called the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, or BQX. And in his State of the City address, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his support for this 16-mile, $2.5-billion streetcar line that would run along the East River and connect Astoria, Queens, with Sunset Park in Brooklyn. (This story on the wonderful Awl website has the details.)

It immediately stirred up debate about whether that transit project, of all transit projects being discussed in New York City, is really the one that makes the most sense and would serve the most people.

I won’t get into that debate. But what’s undeniable is that a trolley to Queens would be a quaint reminder of where New York’s subway, which opened in 1897, has some of its roots laid. And those roots are in Queens. It’s one of my favorite stories in The Race Underground involving one of my favorite characters.

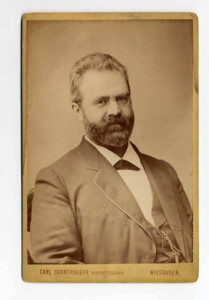

His birth name was Wilhelm Steinweg (that’s him above). He was born on March 5, 1835, the fourth of six children in a tiny German village called Seesen. The father of those children, Heinrich Steinweg, made pianos for a living and one day he dreamed of bringing all of his children into the family business. But when his third son, Charles, was at risk of going to war as Europe was awash in revolutions, Charles fled for New York, joined the piano-making industry there, and wrote home to his family that they should come, too, because the piano factories in the city were thriving.

And so they did. In the summer of 1850, the Steinweg family sailed into New York’s harbor, and not long after that the family name was anglicized into Steinway and a piano manufacturing behemoth was born. One of Charles’ brothers, William Steinway, helped the family grow its business with a manufacturing plant in Queens. It was William’s ability to juggle so many tasks, to disarm anyone he came in conflict with, and to convince politicians to give him what he wanted, that caught the attention of New York politicians in the late 1800s, as efforts ramped up to get a subway approved and built. William Steinway was named to head New York’s Rapid Transit Commission of 1891 and the next decade, his relationship with the brilliant engineer, William Barclay Parsons, and their efforts to bring New York a subway, became an enormous part of Steinway’s legacy.

And it all started in Queens. This is from the great Henry Z. Steinway Diary Project at the Smithsonian: A desire to remove employees from Manhattan’s teeming humanity, particularly organized labor and “the machinations of the anarchists and socialists,” inspired William to purchase 400 acres across the East River in a bucolic, sparsely-populated area of Astoria, New York. With space for much-needed expansion, William set about creating the company town of Steinway where the firm could cast its own piano frames and saw its own lumber. Steinway & Sons pianos are still manufactured at this location. William approached the development of Steinway with characteristic thoroughness, wading through rainy salt meadows in “great India rubber boots” inspecting property, overseeing street surveys, and assessing employee housing construction later advertised as “country homes with city comforts.” Diary entries reflect William’s pride in creating a company town where workers could own brick homes, drink fresh water, and stroll under shade trees on Steinway Avenue—still the main thoroughfare in this part of Queens. He donated land and built a public school, fire house, post office and churches to further his vision. A network of horse-car railroads, streetcars, trolleys, and ferries provided access to the settlement and brought in additional income. What would become North Beach Amusement Park offered “respectable people” an alternative to Coney Island and the chance to experience evening festivities illuminated by the novelty of electric lighting.

And finally, here is the Steinway family at their beautiful stone mansion in Astoria, Queens.

So whether or not the BQX is the best move for New York may be debatable. But what’s undeniable is that a street trolley in Queens would have a certain karma for Gothamites, who owe a great deal of transit debt to a businessman who started in Queens.