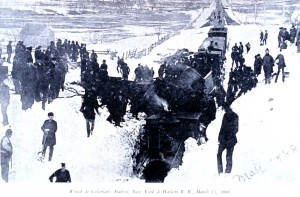

On the bottom of page 13 of The New York Times on Friday, March 9, 1888, there was a brief news item. The headline said: “A blizzard in Minnesota,” and it described a heavy storm moving east, crippling trains along the way. New Yorkers would have had no reason to be alarmed. It was the end of a mild winter, and there was no indication of trouble looming for them.

On the bottom of page 13 of The New York Times on Friday, March 9, 1888, there was a brief news item. The headline said: “A blizzard in Minnesota,” and it described a heavy storm moving east, crippling trains along the way. New Yorkers would have had no reason to be alarmed. It was the end of a mild winter, and there was no indication of trouble looming for them.

“The Blizzard That Changed Everything” is how I titled Chapter 5 in my book, “The Race Underground,” which tells you just how much trouble was about to unfold. The other reason I devote an entire chapter to the Blizzard of 1888 is that it was a pivotal moment in U.S. transit history. Before the blizzard, cities relied on horse-pulled carriages, cable cars and elevated tracks to move their residents. The Blizzard of 1888 forced city officials to acknowledge that they needed to embrace the idea of subways, once and for all, because subways would not be crippled by snow and ice. (The only subway in the world at that point was in London, which opened the Underground in 1863, but by the late 1890s subways would be operating in Boston, Paris, Budapest, Glasgow, Berlin, and a few years later New York.)

As the weekend of March 10, 1888, neared, a department store in New York City, E Ridley and Sons, made the curious decision to buy $1,200 worth of snow shovels, 3,000 of them, not for the current winter, but for the following winter. Stocking up, John Meisinger explained at the time, just planning ahead. A newspaper mocked him, calling him “Snow Shovel John.” Well, “Snow Shovel John” would have the last laugh.

Saturday March 10 was a beautiful spring day up and down the east coast. President Cleveland and his young wife left town for a vacation weekend. Rowers enjoyed the calm waters of the Connecticut River. Crocuses prematurely started to bud. And army sergeant Francis Long looked out his window from the New York City Weather Station and saw a parade of people celebrating the arrival of the Barnum and Bailey Circus on the streets below.

Then things turned.

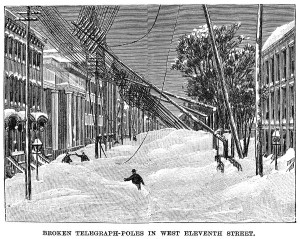

A gentle soft rain late Saturday evolved into a whistling wind and sleet storm. The National Weather Service office closed Saturday night and would not reopen till Monday, a critical 17 hour period that would prove devastating. By Sunday morning the east coast was getting soaked, temperatures were dropping and even a local priest had a bad feeling. “It was as if the unholy one himself was riding in those clouds,” he told his New Jersey parishioners.

By late Sunday it was snowing and it wouldn’t stop for almost an entire week. Measuring how many feet fell was almost impossible. Estimates ranged from 4 feet to 20 feet. The same was true with the fatality total. Some estimated that 400 people died in the Blizzard of 1888, but it’s more likely the storm caused more than 1,000 deaths, because so many people became ill with pneumonia, frostbite and other ailments from the catastrophe and died weeks or months later. Their deaths may never have been blamed on the original cause.

My favorite anecdote from the chapter on the blizzard is this one:

At the New York Infant Asylum north of the city in Westchester County, four hundred children between teh ages of two weeks and six years old, along with 200 unwed pregnant women, normally went through about 800 cans of milk a day, supplied by a nearby dairy. With local roads closed, the blizzard cut them off from the dairy, and without their milk for a week or more, they could have been at risk. But a few days before the storm hit, instead of the typical order of 12 dozen cans of Borden’s canned condensed milk, the asylum was left with 12 gross, or 1728 cans! The cans were for older children usually, but now the infants had to drink them, too, and that concerned the physician in charge, Dr. Charles Gilmore Kerley. Cautiously, the staff diluted the condensed milk with barey water to see if the infants could tolerate it. Not only did they like it, but the babies who had been struggling to gain weight suddenly started to fill out. Because of a simple paperwork error, and one forced experiment, canned evaporated milk for infants, with Dr. Kerley’s urging for the next 50 years, went from being shunned to being embraced.

So not only did the Blizzard of 1888 pave the way for subways to become commonplace, but it benefited undernourished babies into the future, as well. Talk about a lasting impact.