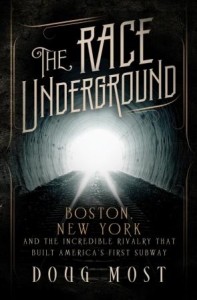

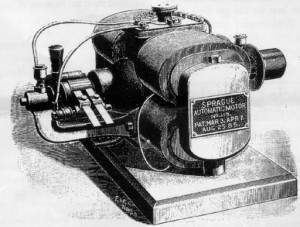

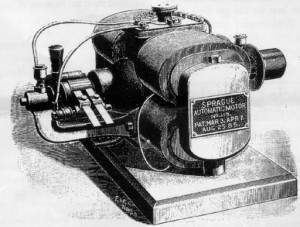

In writing “The Race Underground” I became fascinated with another race, a subplot to the subway story. This race involved engineers from around the world in the early 1880s, all of them determined to build the perfect electric motor. It was a fascinating story with great characters and details, but sadly after months of research I had to cut the chapter from the book. Yes, that hurt.

But there’s no reason I can’t share the chapter here on my blog. A few of these characters receive mention in the book, and one, the last one in this chapter, becomes a major figure in the subway story. Enjoy.

GRASSHOPPERS PLAYED A KEY ROLE in one of the first efforts to build an electric railway. A Kansas farmer named John Henry was left penniless in 1879 when he lost his land, his cattle and two stores to a grasshopper plague and so he set out to design plans for a car that could help farmers. After relocating to Kansas City, he took a job as a telegraph operator and saved money for almost five years, all the while tinkering with his idea. Finally, in 1884, with enough money raised, he borrowed an old mule car and got access to a track. He stretched two copper wires above the track. On top of the wires two small wheels were pulled, or towed, by wires that ran down to the mule car. Henry was all alone on his first test run, and it was a good thing. Sparks flew everywhere, the wheels spun out of control and the mule car derailed and crashed into a hill next to the track. A few days later, Henry made a second run, but it derailed too, only this time Henry along with two interested investors were thrown out of the mule car. It was obvious that he could not control the speed of the mule car with his electric current and when Henry fell back into bankruptcy, it was the end of his experiment.

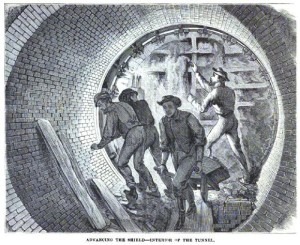

As the 1880s began, the Underground was almost twenty years old, and yet little had changed with it since its opening. “A journey from King’s Cross to Baker Street is a form of mild torture,” is how the London Times described it. After years of tinkering, some of the world’s brightest engineers had begun to make remarkable progress in understanding not only how electricity worked, but what it was capable of doing. Thomas Edison would soon flip a switch in downtown New York, and the area all around Pearl Street and close to Wall Street would light up, an unofficial beginning to the age of electricity.

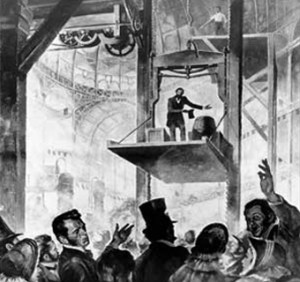

WHEN A GERMAN ELECTRICIAN named Werner Siemens unveiled a 2-horsepower dynamo mounted on to a truck at the Berlin Industrial Exhibition in 1879, it was the breakthrough that marked the beginning of Siemens’ contribution to the field of electricity. Over the course of just two years, Berlin saw the arrival of electric streetlights, an electric elevator and an electric streetcar, all powered by Siemens’ innovation. His achievements even extended to the German language, as he coined the German word for electrical engineering: “Elektrotechnik.” But his contribution to the electric train race was his greatest achievement. At the 1879 exhibition, his invention powered the small truck at a respectable speed, 8 miles per hour, and moved it 350 yards down a track while pulling eighteen passengers. More than 80,000 passengers took the ride, despite warnings that if they touched the third rail that carried 150 volts of electricity, they’d receive quite the jolt. Siemens took the public’s approval at the Berlin exhibition as a sign that they were ready for the real thing. Two years later, a far more ambitious line powered by the Siemens dynamo opened in a small town outside Berlin called Lichterfelde. It carried two dozen people and could zip along at eleven miles per hour, the top speed allowed in town.

The problem with Siemens’ invention was protecting people, especially children, and horses, from shocks as they walked across the rails. Siemens tried to reduce the voltage from 150 to 100, but it still produced a jolt to anyone who got too close, and even more frustrating, the first drops of rain would cause the trains to short circuit and come to a stop. The Siemens dynamo clearly worked as a power source, but perfections were still needed for it to safely operate an entire network of street railways. No metropolis would pour money into a gimmick that might electrocute the very people it was supposed to help move.

In 1884 two men in Cleveland working in the shops of the Brush Electric Company had some profound success. Edward Bentley and Walter Knight had been working for more than a year on an electric street railway. Their trick was to place between two rails an underground wooden conduit to carry two copper conductors. A slot in the conduit connected up to the streetcar and supplied the current needed for the motor that was mounted on the car’s bottom. The rails themselves had nothing to do with the electricity, and on July 26, 1884, Bentley and Knight opened the first electrical railway in America to accept paying passengers. It was an immediate bust.

The streetcars kept jumping the tracks. The wire belts that held the motor to the axle of the car snapped repeatedly. The connection between the conduit and the streetcar was almost always destroyed every time a car derailed. And getting more than one car to operate at a single time never worked. But America was desperate to believe in something that might help cities, and in September 1884, despite all the troubles in Cleveland, a New York millionaire invested his fortune in the Bentley-Knight Electric Railway Company. And for a few years, it paid off.

The Bentley-Knight company expanded, and landed contracts to build electric railways in New York, Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. In New York, its $214,000 bid to build a three-mile track for 37 street railway cars along Fulton Street downtown was accepted. The company sales pitch was that an electric railway system was cheaper over the long run than steam, cables or horses, cleaner than all of them, and faster and safer, too. The company estimated that to start up a five-mile double track, with forty cars, cost about $803,000 with cable, $462,000 for electric and $204,000 for horses. But to operate the tracks annually, it would cost about $100,000 for horses or cable, and only $52,000 for electric, a significant savings over time. Plus, if a city already had tracks laid, Bentley-Knight vowed to simply use those tracks rather than replace them.

It seemed so promising, but Bentley and Knight’s underground conduit never quite worked to perfection and after repeated use day after day it would break down, especially in bad weather. If they had been willing to make one concession to a new innovation that had come along, and tried installing overhead wires to carry electricity rather than putting the electricity underground, Bentley and Knight might have become pioneers in urban transit. But they were convinced that overhead wires were doomed, that the public would consider them unsightly and dangerous and not worth the investment.

AS CLOSE AS BENTLEY AND KNIGHT CAME to putting all the pieces together, Leo Daft came closer. A stubborn Englishman with a long face and a bushy gray beard, Daft opened a three-mile line in Baltimore that, for a brief period, was America’s first commercially run electric streetcar operation to work for more than just a few days or weeks. It was quite the adventure.

Daft was born in England in 1843 and tinkered as a young boy with telegraphs and photographs. They might have seemed like odd hobbies, except his father was an engineer who helped build ships and bridges and encouraged his son to work with his hands. When Daft left England and came to the United States in his early twenties, he opened his own photo studio outside New York City, but grew bored and turned back to engineering, and specifically the challenges of electricity. In Greenville, New Jersey he opened the Daft Electric Light Company, but he was really more intrigued by the problem steam locomotives were having. The steam trains had immense power, but slipped easily off their tracks. Daft’s early experiments led him to believe that electricity flowing through rails acted like a magnet and helped keep the wheels from slipping off. He grew determined to figure out a way to design an electric locomotive, and to use no more than 25 volts, reducing the risk of dangerous jolts to pedestrians and horses.

His first test came in Saratoga, New York on November 24, 1883, when he invited a list of lawyers, potential financiers and newspaper reporters to see the Ampere, a two-ton locomotive he had built in about six months and named after Andre-Marie Ampere, the famous French electrician. Its 25-horsepower motor was as powerful as he had hoped, and it ran on three rails, with the third one carrying the current that came from a dynamo, not unlike the one Werner Siemens had perfected. For his test run, Daft’s locomotive, with him manning the controls, managed to pull a single train car carrying 75 passengers smoothly up a steep incline at eight miles per hour. Success! And if he had stopped at the top, maybe Daft would have gone on to become the king of the electric streetcar. But he was overeager, because on his way down the hill he allowed his train to accelerate to fifteen miles per hour. The Ampere could not handle a sharp turn and it flew off the rails and landed on its side. Nobody was seriously hurt, and a reporter on the scene recalled Daft’s words: “We were going too fast.” Not only was the locomotive damaged, but Daft’s credibility was hurt, too.

It was difficult to ignore the irony when a steam locomotive was needed to bring back what remained of Daft’s experiment. But instead of losing confidence, he emerged feeling bolder. Within months Daft had two new locomotives up and running, and one of them, the Pacinotti, caught the attention of the Union Passenger Railway in Baltimore. Horses there were struggling with one particularly winding and hilly line in his city and the hope was that Daft’s contraption might just solve the problem.

Daft had little doubt his machine could conquer the hills, but he struggled to convince city officials in Baltimore. They brought in a scientist to examine the challenge Daft faced, and he came back with a daunting report. “The man who undertakes to operate this section by electricity in the present state of the art is either a knave or a fool.” If the Baltimore officials were hesitant before the report, they were flat out opposed after it. It was only when the general manager of their system threatened to quit if they did not give Daft a chance that they relented. They offered Daft a contract that any sane businessman would have laughed away. They told him he could electrify the hilly, three-mile line, but he had to use his own locomotives and pay for the entire experiment. Only if it worked for a full year would they buy his equipment. Daft agreed without hesitation.

On August 9, 1885, at one o’clock in the morning to avoid any embarrassing slip-ups in full view of the public, Daft conducted a trial of his system. It worked so beautifully that the next day it opened for paying passengers. They boarded the same 16-foot horse cars they rode on the other lines, but instead of a team of horses out front, there was a small black and boxy locomotive. Before anybody had a chance to wonder about their safety, they were being zipped down the Hampden branch at twice the speed the horses used to pull them. Daft was deliriously proud of himself and for years after his line opened, he boasted about how he had defied the opinion of that skeptical scientist, who had paid to ride Daft’s electrified line and conceded he’d been wrong.

True to the contract he’d signed, Daft was reimbursed for his efforts one year after his line began accepting paying passengers. But even though the tracks worked, they were flawed. Steady rains short circuited the system. And the low-voltage that Daft had started out using was not enough over the long term and when he increased the power to 120 volts, cats and dogs and even chickens that touched his third rail let out yelps of pain and often died from the shocks. Horses were not injured, but they seemed to sense the danger and either stepped gingerly over the tracks or refused to go near them. For more than three years, Daft’s electric streetcar line in Baltimore did just as he promised. It carried paying passengers up and down through a steep set of hills, and took an enormous burden off of horses in the city. By placing his electric motor at the front of the car rather than underneath it, as other inventors would do, his passengers felt safer knowing they could see the source of power that was moving them. But when the third rail became such a tiresome concern to city officials, they forced Daft to remove it at the major crossings and replace it with heavy gas pipes that were hung over the tracks. That only caused greater problems, and eventually in 1889, when Daft refused to make more changes and sold off his electric railway patents, his boxy locomotives were garaged and replaced by the old reliable standby, horses.

IF DAFT HAD A RIVAL, it was Charles J. Van Depoele, whose invention experienced more widespread acceptance. Growing up in Belgium, Van Depoele saw how the London subway had generated such excitement across Europe when it opened. He first took an interest in electricity while in college, experimenting with battery power, and when he came to the United States in 1869 and started his own furniture making business in Detroit, he continued to tinker on the side with some electrical experiments. Soon he was able to light his own shops and in 1881 he abandoned furniture altogether to set up the Van Depoele Electric Light Company.

Like many inventors of the day who enjoyed imagining the possibilities of electricity, he turned away from lighting and focused on electric motors, and more specifically an electric railway. His ideas were similar to the ones designed by Bentley and Knight, except Van Depoele was willing to look up instead of down for his power source. He attached a pole to the roof of his streetcar, which connected to an overhead conductor that ran between trolley poles. A spring at the base of the pole kept it in contact with the wire overhead. In the fall of 1883, Van Depoele installed an electric railway at the Chicago Industrial Exposition to move people into the grounds of the exhibition, and the following summer he built an identical one at the Toronto Agricultural Fair. One motorcar pulled three trailing cars, each able to carry sixty people, and on some days in Toronto ten thousand passengers rode his railway one mile to connect with a horse car line downtown. Quickly Van Depoele starting receiving interest from other cities. South Bend, Indiana, New Orleans, Montgomery, Alabama, Appleton, Wisconsin, Detroit, Minneapolis, they all wanted contracts with him, even though his idea had only been used at these exhibitions and had never been successfully tested on a large scale. No matter. Cities were desperate and he obliged them.

Between 1886 and 1887, Charles Van Depoele was well on his way to making history. He had a dozen electric street railways installed, sixty miles of track and nearly one hundred cars in use around the country. Nobody was close to his growth, and like his competitors he always emphasized the long-term cost savings a city would see with an electric railway. His Montgomery system, the largest of his operations, cut the city’s transportation costs by one-third and allowed it to move more passengers than horse cars and make more money. If he had any problem, it was keeping up with production demands.

But Van Depoele himself was not convinced of his own system’s merits. He was skeptical it would work on a larger scale, even as he was being flooded with requests to expand. And he wasn’t sure there was great money to be made in electric street railways. By 1887, Van Depoele was poised to do for electric street railway what Edison had done for electric lighting. But instead he wanted out. He went looking for a buyer. When Thomson-Houston, the same company that had snatched up Bentley-Knight, approached Van Depoele in the spring of 1888 and offered to buy him out and give him a permanent job in its railway department, he accepted. His company received a royalty of $25 for every streetcar that was equipped with his invention and the inventor himself got $5 per car. He was satisfied, even though Thomson-Houston had not been his first choice to take over his operations.

For several years, Van Depoele had been following the progress of a former naval engineer who was making great strides toward perfecting the electric street railway. Van Depoele was certain that if anybody was going to succeed where the others had failed, it would be Frank Julian Sprague.

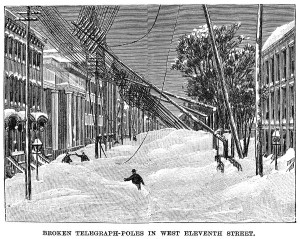

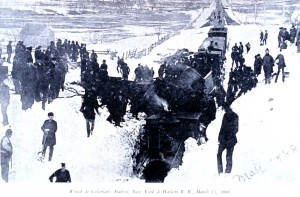

It seems appropriate that on Monday evening, February 9, 2015, a certain box arrived at our house. On a day when an epic amount of snow is piled high outside, and on a day when our governor has announced all trains and subways and buses will be shut down tomorrow because of our blizzard, this box had particular significance to me. It’s exactly one year since “The Race Underground” came out, and today the paperback version is released (yes, if you still don’t have the hardcover, the paperback is cheaper and it looks great, complete with a New York Times quote on the cover!). Chapter 5 is titled “The Blizzard That Changed Everything,” and it tells the story of a boy named Sam Strong, who nearly died trying to run a simple errand for his aunt in the Blizzard of 1888. That storm was pivotal in how it forced city officials from New York to Boston to take a long hard look at their transit systems and decide they’d be better off running underground than above. Subways in America were born. One can only hope that the Blizzard of 2015 forces today’s officials to take an equally long hard look at their transit system and make some changes that are equally momentous. On that note, if you need a great read this winter, “The Race Underground” paperback is here! Thanks all.

It seems appropriate that on Monday evening, February 9, 2015, a certain box arrived at our house. On a day when an epic amount of snow is piled high outside, and on a day when our governor has announced all trains and subways and buses will be shut down tomorrow because of our blizzard, this box had particular significance to me. It’s exactly one year since “The Race Underground” came out, and today the paperback version is released (yes, if you still don’t have the hardcover, the paperback is cheaper and it looks great, complete with a New York Times quote on the cover!). Chapter 5 is titled “The Blizzard That Changed Everything,” and it tells the story of a boy named Sam Strong, who nearly died trying to run a simple errand for his aunt in the Blizzard of 1888. That storm was pivotal in how it forced city officials from New York to Boston to take a long hard look at their transit systems and decide they’d be better off running underground than above. Subways in America were born. One can only hope that the Blizzard of 2015 forces today’s officials to take an equally long hard look at their transit system and make some changes that are equally momentous. On that note, if you need a great read this winter, “The Race Underground” paperback is here! Thanks all. It seems appropriate that on Monday evening, February 9, 2015, a certain box arrived at our house. On a day when an epic amount of snow is piled high outside, and on a day when our governor has announced all trains and subways and buses will be shut down tomorrow because of our blizzard, this box had particular significance to me. It’s exactly one year since “The Race Underground” came out, and today the paperback version is released (yes, if you still don’t have the hardcover, the paperback is cheaper and it looks great, complete with a New York Times quote on the cover!). Chapter 5 is titled “The Blizzard That Changed Everything,” and it tells the story of a boy named Sam Strong, who nearly died trying to run a simple errand for his aunt in the Blizzard of 1888. That storm was pivotal in how it forced city officials from New York to Boston to take a long hard look at their transit systems and decide they’d be better off running underground than above. Subways in America were born. One can only hope that the Blizzard of 2015 forces today’s officials to take an equally long hard look at their transit system and make some changes that are equally momentous. On that note, if you need a great read this winter, “The Race Underground” paperback is here! Thanks all.

It seems appropriate that on Monday evening, February 9, 2015, a certain box arrived at our house. On a day when an epic amount of snow is piled high outside, and on a day when our governor has announced all trains and subways and buses will be shut down tomorrow because of our blizzard, this box had particular significance to me. It’s exactly one year since “The Race Underground” came out, and today the paperback version is released (yes, if you still don’t have the hardcover, the paperback is cheaper and it looks great, complete with a New York Times quote on the cover!). Chapter 5 is titled “The Blizzard That Changed Everything,” and it tells the story of a boy named Sam Strong, who nearly died trying to run a simple errand for his aunt in the Blizzard of 1888. That storm was pivotal in how it forced city officials from New York to Boston to take a long hard look at their transit systems and decide they’d be better off running underground than above. Subways in America were born. One can only hope that the Blizzard of 2015 forces today’s officials to take an equally long hard look at their transit system and make some changes that are equally momentous. On that note, if you need a great read this winter, “The Race Underground” paperback is here! Thanks all.