It was a drizzly evening, but that didn’t keep the crowd away. It was billed as a “conversation” about transportation between myself and Michael Dukakis at the John F. Kennedy Library Friday evening, April 4, and more than 350 people showed up. There is no doubt the former Massachusetts governor was the big draw. I was happy to tag along for the ride with the most famous Green Line rider in Boston!

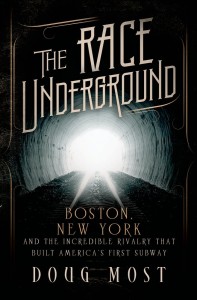

We had emailed beforehand and he graciously praised my book, “The Race Underground” as a great read: I am about halfway through your book– somebody gave it to me as a gift– and it is one great read. I thought I knew something about Massachusetts history and its transit system, but nobody ever told me that a guy named Henry Whitney from Brookline not only played a key role in the whole thing but was responsible for turning Beacon St. in Brookline into a two hundred foot boulevard with a street car down the middle of it .

We met in the lobby of the JFK Library, where he was sitting with friends and his wife, Kitty. Both of them look terrific and he seemed genuinely excited about the event. As the crowd filed in, he regaled my wife, Mimi, and I with stories about personalities in his administration and what he loved most about the book (the details about Brookline, especially, since they live there).

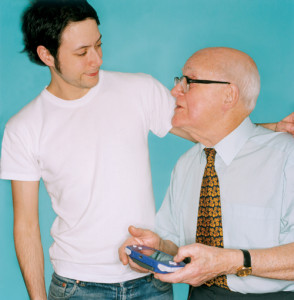

Inside the auditorium, every seat was filled, thanks to wonderful promotion by The Boston Globe and the JFK Library. My parents had called to say they were sadly running late thanks to a flat tire while driving up from Rhode Island, so two seats were saved for them in the front row next to my wife and mother-in-law (my parents arrived a few minutes after Dukakis cracked a joke about them being from New York — proof of how closely he had read my book, right through the epilogue). Just before going on stage, I asked Gov. Dukakis if he’d indulge me in the silly trend of the day, a selfie, and he obliged, and then we took our seats on stage.

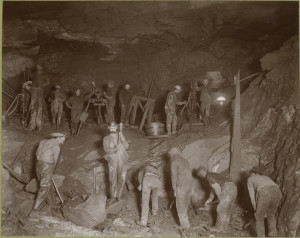

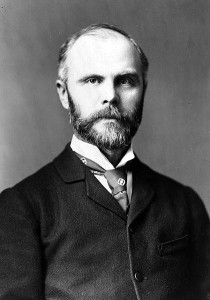

Amy Macdonald from the JFK Library introduced us, and then, as we’d agreed, I went first and talked about the back story behind the book. I spoke about some of the key characters, like brothers Henry and William Whitney, engineers Frank Sprague and William Barclay Parsons, piano manufacturing giant William Steinway, and others.

The governor went next and his first words were so gracious. He said he had no obligation to promote the book (true!) but then proceeded to say, “Buy this book! It’s a great read!” He then talked about what happened with transit in Massachusetts after World War II, especially highways and trains. He talked about riding the wooden trolley cars through Boston with Kitty, and about the political shenanigans he dealt with during his tenure in office. He often pointed at friends and former staff members of his in the audience. We went back and forth for about 45 minutes and ended with questions from the packed house, followed by a book signing at which both of us signed copies of the “The Race Underground” for a long line of people. They were happy to get my signature, but REALLY happy to get his.

And when we were done, I turned to him, shook his hand, said thank you for agreeing to do the event with me. And then I asked him to sign my book, too. Great evening. (And yes, that’s Mimi, left front row below.)

Sure, it’s a cliche to say it’s an honor to just be nominated for something. So that makes me a cliche-monger, I guess, because it really is an honor for “The Race Underground” to be nominated for the very prestigious Kirkus Prize in non-fiction. I was thrilled to get a starred review from Kirkus when the book came out and so that review leads to the nomination (winners will be announced in October).

Sure, it’s a cliche to say it’s an honor to just be nominated for something. So that makes me a cliche-monger, I guess, because it really is an honor for “The Race Underground” to be nominated for the very prestigious Kirkus Prize in non-fiction. I was thrilled to get a starred review from Kirkus when the book came out and so that review leads to the nomination (winners will be announced in October).